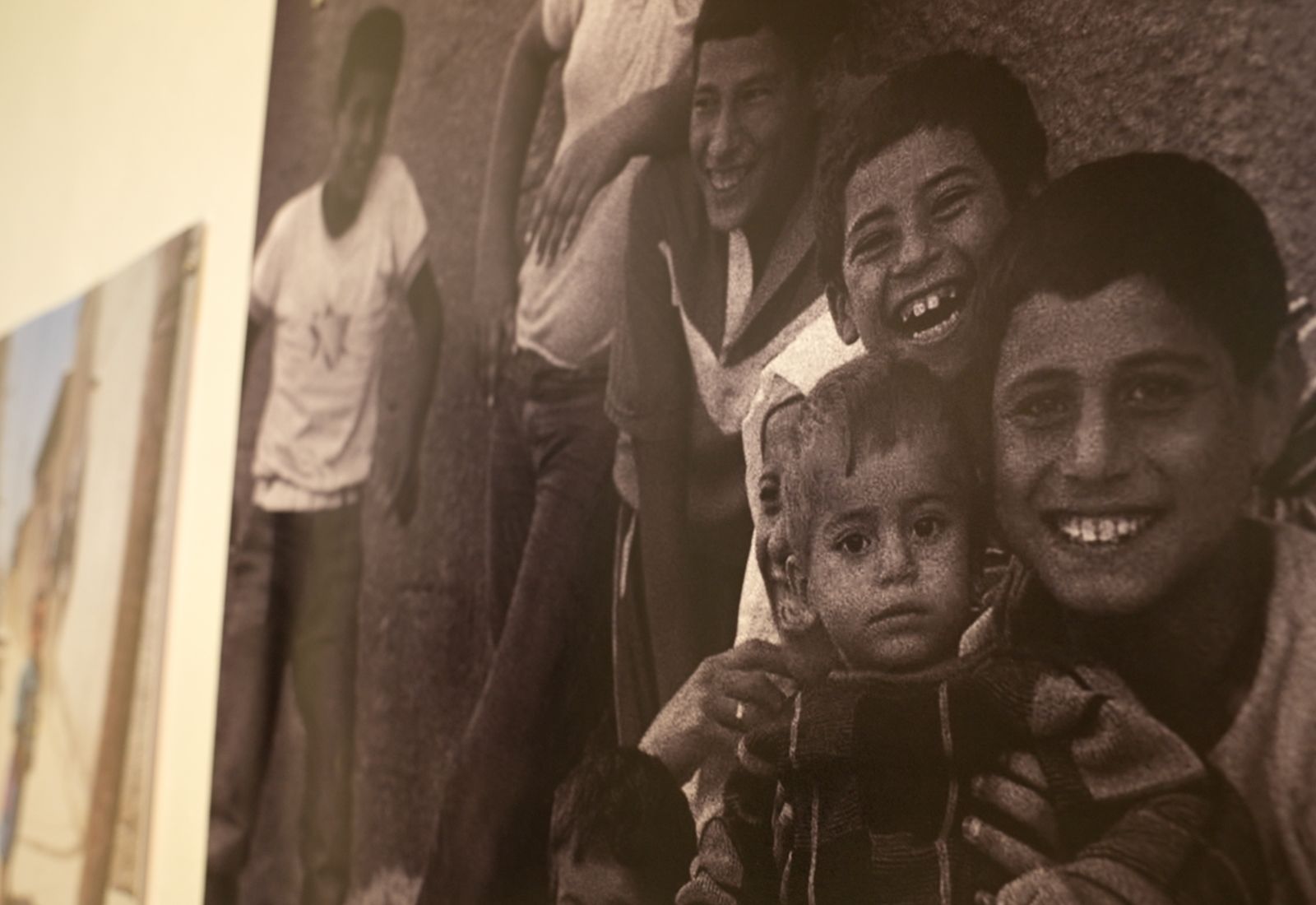

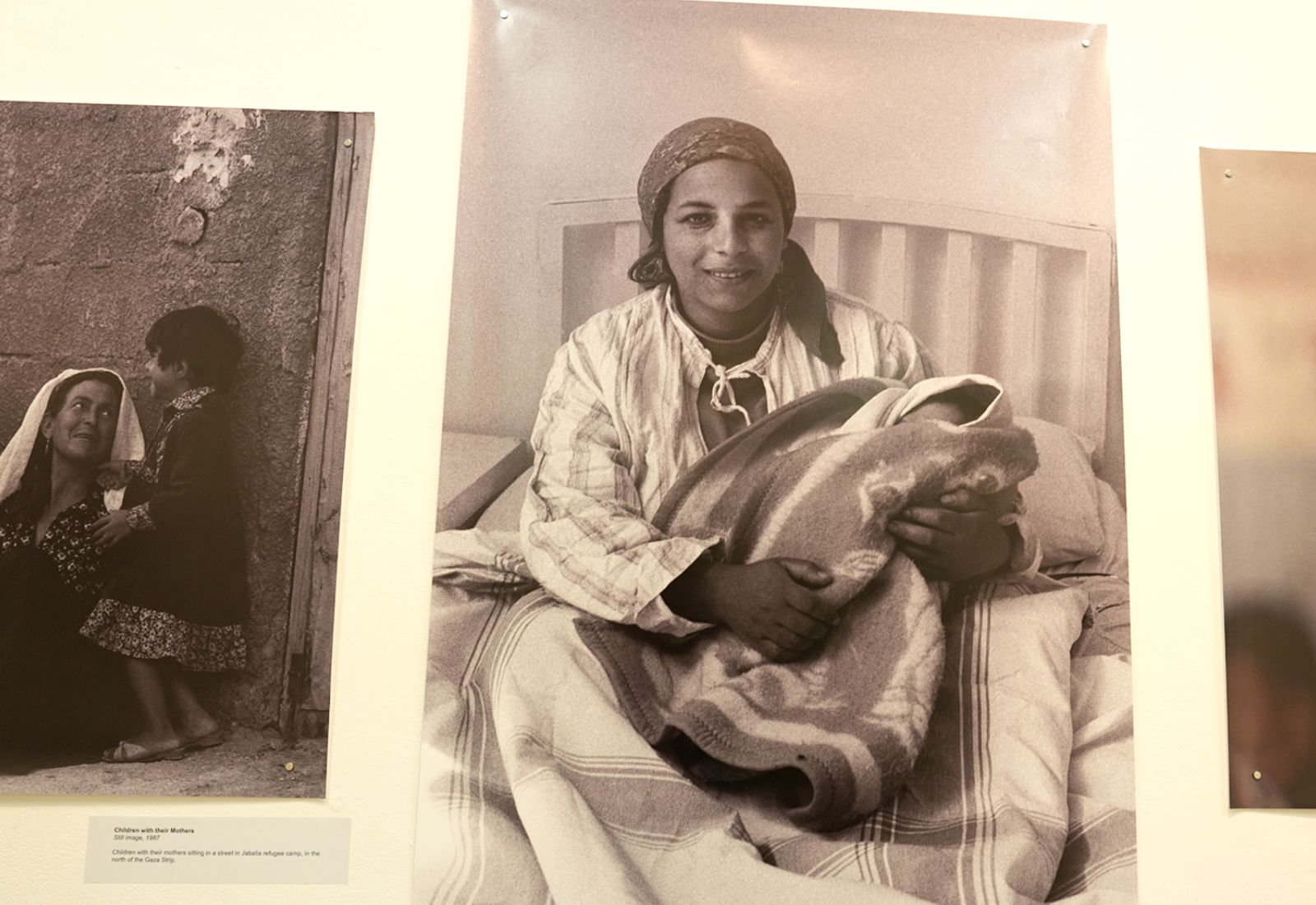

If a picture is worth a thousand words, The Many Lives of Gaza exhibition could write several trilogies.

Displayed at the Bermondsey Project Space earlier this month, the exhibition told the tale of Palestine through a nostalgic Gazan lens.

Prior to the Nakba in 1948, meaning “catastrophe” in Arabic, the Gaza Strip was an area of fertile land and abundance, composed of vibrant fishing towns and villages.

Following this upheaval, some 750,000 Palestinians were displaced. Zionist militias killed at least 15,000 local residents, ethnically cleansing more than 500 towns. In Gaza alone, some 130,000 refugees arrived, having fled ransacked villages.

The Many Lives of Gaza captures this aftermath vividly, making use of multiple media forms.

Archived photographs from the Palestinian Museum in the West Bank display the reality of refugee camps. Video interviews with survivors relay anecdotes of the past.

Pieces by Palestinian artists and infographics also dot the walls, letting visitors engage with key facts and figures.

“It’s this combination of very heartfelt photography but also hardcore facts – I think that’s a strength of the exhibition,” says Jordanian Filipina-American writer and editor Malu Halasa.

“It’s important to put Gaza into perspective, and to think about it differently. Looking at the news, you hear about what’s happening in terms of the war, but it’s rare that we’re hearing Gazan voices or seeing Gazan faces.”

According to Halasa, the key to understanding the real context lies in creative spaces. “The amplification of Palestinian lives, voices, experiences is very important. In culture and art, you learn more about people. These are platforms where people speak for themselves instead of having the intermediary of the news or an academic.”

For exhibition co-curator Dr Meg Peterson, this resonates. “There’s an educational element to it. “[We’re] trying to uncover the layers so people don’t just see images of conflict and destruction. It’s also seeing images of life and joy – that side of Gaza.”

“There’s a much deeper story behind the images. People want to know more about the people who are captured, but unfortunately we just don’t know where they are.”

Through expression and emotion alone, Peterson hopes to connect to people’s humanity. Her main message is one of “solidarity and action”.

“There’s so much that you can do on a small scale to make a really big difference, and everyone should feel a responsibility to be a part of that change.”

This is a cause of special significance for co-curator Nadine Aranki, who is herself Palestinian. Having grown up in Ramallah in the occupied West Bank, the reality of life under occupation is especially close to home.

“It’s like we are undergoing slow mass murder. There are many justifications out there by the Israeli propaganda about why they are committing this genocide. In the West Bank, we have also seen a rise of Israeli soldiers killing people.”

Aranki seeks to dispel this dehumanisation and violence by drawing focus onto the subtle and everyday. “We try to tell the story of the daily life of Palestinians in Gaza. Visitors are really fascinated by this context. It’s giving them new information.”

As for her wishes for the future, Aranki believes in the power of art to make change.

“This exhibition is really important at this specific moment of time. It’s trying to break through and shift the narrative of what it means to be Palestinian.”

“A lot of the time, this is presented as a complicated question, but it’s not. It’s very simple. We want a ceasefire. We want our people to live.”